| Julian Faulhaber Corona |

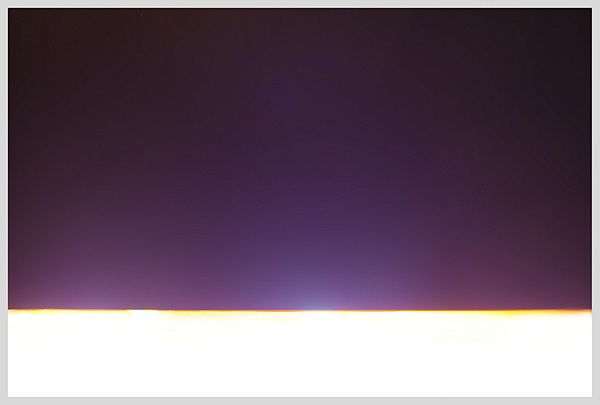

Julian Faulhaber

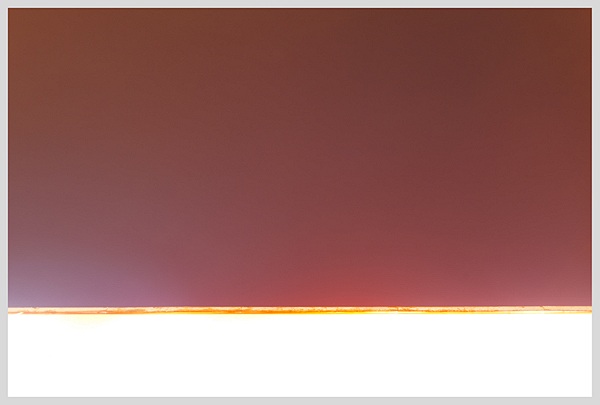

- Corona Nr.I,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

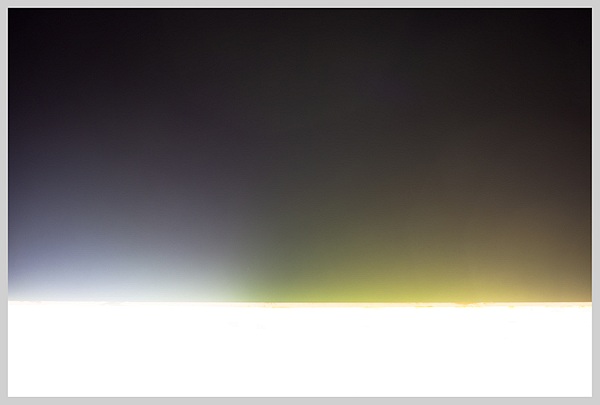

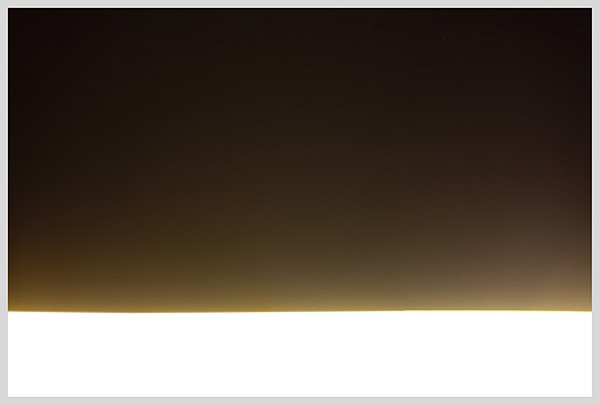

Julian Faulhaber

- Corona Nr.II,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

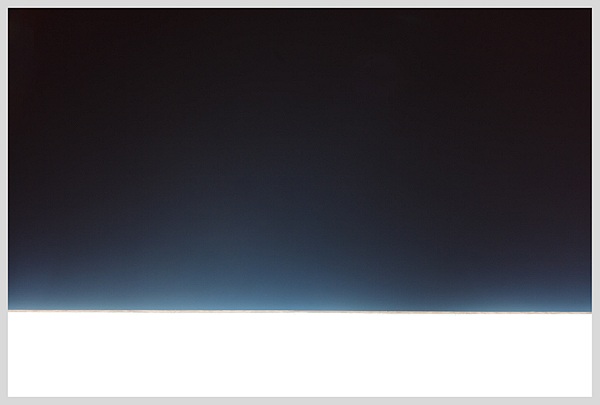

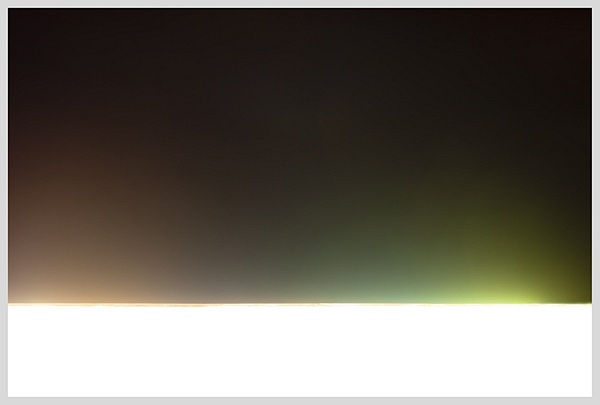

Julian Faulhaber

- Corona Nr.III,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

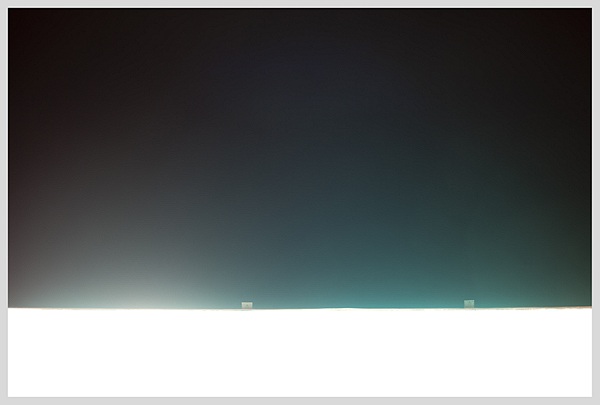

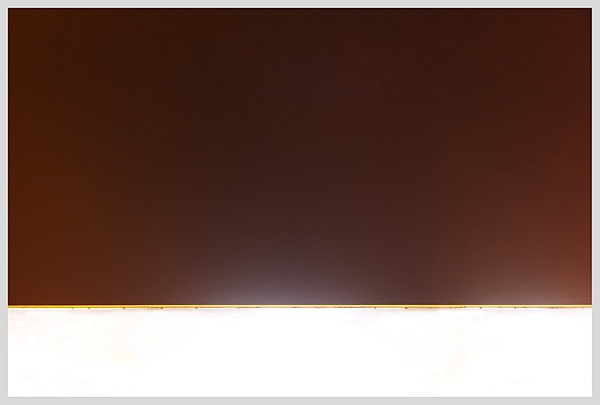

Julian Faulhaber

- Corona Nr.IV,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

Julian Faulhaber

- Corona Nr.V,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

Julian Faulhaber

- Corona Nr.VI,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

Julian Faulhaber

- Corona Nr.VII,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

Julian Faulhaber

- Corona Nr.VIII,

2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm

Julian Faulhaber - Corona Nr.IX, 2014, Fine Art Print, 90 x 135 cm © Julian Faulhaber, VG Bildkunst Bonn |

| Corona Erscheinung eines Bildes Corona – so hat Julian Faulhaber seine neue in Kairo entstandene Fotoserie genannt. Was ihn inspiriert hat, sind die großen beleuchteten Werbetafeln, die hoch über den Verkehrsadern der Stadt thronen. Diese Tafeln dominieren ihre Umgebung nicht nur durch ihre schiere Größe, sondern auch durch ihre grellen Farben, die im Kontrast zur vom Smog und Wüstenstaub bedeckten Stadt stehen. Die strahlende Herrschaft der leuchtenden Werbeflächen erinnert an eine Krone und gleichzeitig an eine urbane Vision Bruno Tauts: Der expressionistische Architekt und Stadtplaner entwickelte 1919 das Konzept einer Gartenstadt, in deren Zentrum sich weithin sichtbar ein Kristallturm über der Stadt erhebt. Diesen Kristallturm nannte Taut die „Stadtkrone“, ein zweckfreier Bau, der einfach „nur schön“ sein sollte. Bei der Entwicklung seines Konzepts ließ sich Taut von Städten und Denkmälern aus verschiedenen Epochen und Kulturen inspirieren. Neben Athen mit der Akropolis und Bangkok mit dem Tempel Wat Arun verweist Taut auch auf ein Bild von Kairo, der „Mutter aller Städte“ – hinter der mit Häusern und Moscheen zugebauten Stadt erheben sich zwei mächtige Pyramiden. Faulhabers Wahrnehmung der Stadt Kairo wurde zunächst geprägt von den vielen Hotels und Wohnblöcken, die den Blick auf die Denkmäler der antiken Kultur versperren, längst ist die Stadt mit ihrer chaotischen und ausufernden Bebauung bis an den Fuß der Pyramiden vorgedrungen. Obwohl sie immer noch einen mächtigen Eindruck hinterlassen, sind die Grabmäler nicht mehr die Krone der Stadt. Faulhaber erhebt die Werbetafeln zur Stadtkrone, mehr noch den Lichtschein, den sie nachts ausstrahlen. Diese Assoziation, das image, verwandelte Faulhaber in ein Bild, das picture. Er fotografierte nachts, wenn die Neonröhren die Werbeflächen besonders hell und klar aus der Dunkelheit hervorheben und der Widerschein des Lichts die Farben transformiert. Die so entstandenen Bilder zeigen weder die Produkte noch das Setting der Werbung. Auch die Umgebung bleibt dem Betrachter verborgen, keine Stadt als Hintergrund. Faulhaber interessiert denn auch nicht das Dokumentarische, die Materialität oder das Narrative der Situation, sondern vielmehr deren poetische Abstraktion: die Verfärbung des dunklen Himmels durch das Licht und das Eigenleben, das die beleuchtete Fläche in der Dunkelheit entwickelt. Die Bilder sind immateriell und in Gänze abstrakt. Eine unscharfe Kontur trennt große dunkle von schmalen überbeleuchteten Farbflächen. Sie beeindrucken durch ihr breites Farbspektrum, das man in Kairo bei Tageslicht vergeblich suchen würde. Die satten, dunklen Farben mit einem Hauch von vintage lassen an die späten Bilder Mark Rothkos denken. Faulhabers Corona-Serie besticht durch eine formale Eleganz, die in ihrer besonderen Farbgebung, vor allem aber in der Reduktion liegt: Hier wird nichts erzählt, nichts inszeniert. Der Betrachter findet auch keinen Kommentar zum „ästhetischen ´Konsum´, der für gewöhnlich den Kreislauf von Waren, Wörtern und Zahlen vervollständigt“, wie es Jacques Rancière in seiner Politik der Bilder formulierte. Stattdessen konzentriert sich Faulhaber auf die Konstellation von image und picture, eine Konstellation von dem Gesehenen und Gedachten. So wird das Ergebnis, Corona, nicht zur bloßen Abbildung, sondern zur Aufforderung ein neues Bild zu denken. Kasha Bittner Corona Making a Picture Appear Corona, Julian Faulhaber’s new photographic series made in Cairo, was inspired by the large illuminated advertising panels throning high above the city’s traffic arteries. These billboards dominate their environment not only through sheer size, but also through their glaring colors, which provide a stark contrast to the smog and desert dust engulfing the city. The radiant reign of the gleaming advertising signs reminds one of a crown and at the same time of one of Bruno Taut’s urban visions: In 1919, the expressionist architect and urban planner developed the concept of a garden city, in the center of which a crystal tower rose high above and clearly visible from afar. Taut called this crystalline structure the Stadtkrone, or city crown, which was not meant to serve any function, but “just be beautiful.” In his concept development, Taut let himself be inspired by cities and monuments of different epochs and cultures. Besides Athens with the Acropolis and Bangkok with the Wat Arun Temple, Taut referred to a picture of Cairo, “Mother of all Cities,” in which two majestic pyramids rise behind a city packed full with houses and mosques. Faulhaber’s perception of Cairo was initially shaped by the many housing blocks and hotels obstructing the view of the ancient cultural monuments; with sprawling, chaotic development, the city has long crept onto the feet of the pyramids. While they still leave a powerful impression, the tombs have ceased to be the crown of the city. Faulhaber instead confers the title of city crown to the billboards, or even more so to the light they radiate at night. Faulhaber transforms this association, the image, into the picture. He photographed at night, when the neon lights bring out the advertising panels especially brightly and clearly and the reverberation of the light transforms the colors. The resulting pictures show neither the products nor the setting of the advertisements. Even the surroundings remain hidden from the viewer, there is no cityscape in the background. After all, it is not the documentary, the materiality or the narrative of the situation which intrigues Faulhaber, but its poetic abstraction: the light discoloring the dark sky, the illuminated space developing a life of its own in the dark. The pictures are immaterial and entirely abstract. A fuzzy contour divides large, dark color areas from smaller, overexposed ones. The wide spectrum of colors is impressive and in daylight could not be found anywhere in Cairo. The saturated dark colors with a ‘vintage’ touch are reminiscent of Mark Rothko’s late works. Faulhaber’s Corona series is distinguished by a formal elegance which derives from its particular coloration, but especially from reduction: There is no narrative, no staging. The viewer will look in vain for a commentary on “aesthetic ‘consumerism,’ which usually completes the cycle of merchandise, words and numbers,” as Jacques Rancière wrote in The Politics of Aesthetics. Instead, Faulhaber concentrates on the constellation of image and picture, a constellation of what is seen and what is thought. As a result, Corona is not mere representation, but a request to think a new picture. Kasha Bittner (Translation by Simone Schede) |