Neontigers (Shenzhen)

Pressetext - Neontigers

Press Release - Neontigers

Peter Bialobrzeskis Neontigers

Neon ist ein Naturprodukt. Und ein rares dazu.1,8 x10-3 Volumenprozent, einfacher ausgedrückt: 0,002 Prozent – mehr gibt es nicht von diesem Gas, zumindest nicht in der Atmosphäre unseres Planeten. Syntetische Herstellung? Unmöglich. Das ist das Großartige am klassischen Neonlicht: Obwohl es für absolute Künstlichkeit und kalte Modernität steht (ganz anders als die funkelnden Gaslaternen in Julius Rodenbergs Paris), ist der Grundstoff der Röhre nicht künstlich herstellbar.

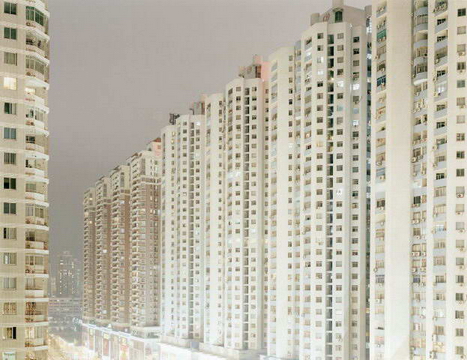

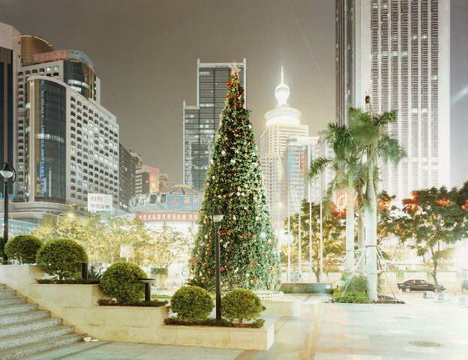

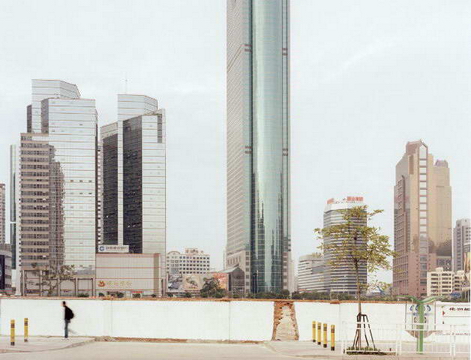

Ähnliches gilt für Peter Bialobrzeskis magische Fotografien in Neon Tigers. Auch sie sind, wenn man so will, natürlichen Ursprungs. Wie digitale Fiktionen wirken sie, sind jedoch analog. Kein Mausklick hat sie je verfremdet, kein Bildbearbeitungsprogramm sie berechnet. Wie Neonröhren lassen Bialobrzeskis Bilder das Chaos unter ihrer Oberfläche nur erahnen. Die Menschenmassen, die sich durch diese Megastädte bewegen, sind oft so unsichtbar wie die strömenden Elektronen in der Lampe, deren Kollisionen mit den Gasatomen den Leuchtstoff erst zum Glimmen bringen. Weil die Menschen so rar sind in diesen Fotografien, zieht das Kunstlicht in der Dämmerung den Blick an. Manchmal strahlen die Leuchtstoffröhren Asiens aus Bialobrzeskis Bildern, als glühten die1,8 x10-3 Volumenprozent Neon auf einmal.

Nicht wie es da ist, sondern wie es sein könnte

„Mir geht es nicht darum zu zeigen, wie es da ist“, sagt Peter Bialobrzeski. „Ich will zeigen, wie es sein könnte, wenn ich es fotografiere.“ Begriffe wie „Traum“ und „Fiktion“ fallen oft, wenn er über Neon Tigers redet. Immer wieder bezieht er sich auch auf Filme, Bücher, Computerspiele: Blade Runner etwa, Krieg der Sterne, William Gibsons Romane Neuromancer und Mona Lisa Overdrive oder das Computerspiel Sim City. In Bialobrzeskis Kopf sind all diese Bilder, Mythen, und Fantasien miteinander vernetzt, und er will, dass es dem Betrachter genauso geht. Er will, dass die Fakten irgendwann verschwinden und die Illusion entsteht, all diese Städte wären eine Stadt. Eine neue Stadt. Eine Stadt, die auf keiner Landkarte verzeichnet ist, außer in dem Atlas, den Neon Tigers entwirft.

„Mir geht es immer darum, dass das Bild in der Lage ist, zu verzaubern“, erklärt der Fotograf. Klar ist auch: In erster Linie hat er sich von dem Projekt verzaubern lassen, von einem imaginären Asien, das sich ihm als hypermoderne Traumwelt darstellt. Allerdings fotografiert er diese Welt mit der altmodischsten Apparatur, die man sich vorstellen kann: der analogen Plattenkamera. „Wenn ich’s am Computer machen würde“, sagt er, „wäre es langweilig.“ Wer sich in die Bilder von Neon Tigers versenkt, stellt sich diesen Fotografen als eine Art fliegendes Auge vor. Kindliche Fantasien entstehen: von einem Mann, der durch Hochhausschluchten schwebt, schwerelos, ohne Limits – wie in einem Play-Station-Universum. Natürlich ist der Alltag anders. Bialobrzeski kommt in einer Megastadt an, sucht sich ein zentral

gelegenes Hotel, checkt ein. Jeweils am Vormittag läuft er los. Nimmt nicht die Kamera mit, die ist zu schwer, hat nur einen Notizblock in der Hand. Er geht durch die Straßen von Shanghai, Shenzhen, Kuala Lumpur, wandert in konzentrischen Zirkeln um das Hotel. Macht sich Notizen. Versucht, irgendwie nach oben zu gelangen – etwa, indem er über Parkdecks in die Höhe steigt. Oder indem er Public-Relations-Beauftragte von Hotels und Wolkenkratzern davon überzeugt, ihn herauf zulassen in die Vertikale dieser Metropole. Wenn er ein paar Orte, ein paar gute Perspektiven gefunden hat, geht er zurück ins Hotel. Isst. Ruht sich aus. Zieht dann am Nachmittag mit der Kamera los – immer zur gleichen Uhrzeit, immer zwischen 16 und19 Uhr. Drängt sich mit seinem Stativ in einen Aufzug und schwebt nach oben. Baut das Stativ auf. Belichtet. Manchmal vier, manchmal acht Minuten lang.

Daguerre fotografierte1839 den belebten Boulevard du Temple in Paris. Weil er so lange belichten musste, verschwand die hektische Masse von Fußgängern und Fahrzeugen von seinem Bild. Nur ein einziger Mann war zu sehen: der hatte gerade innegehalten, um sich die Schuhe putzen zu lassen. Zwar haben die Städte, um die es Bialobrzeski geht, kaum noch etwas mit der europäischen Großstadt des19. Jahrhunderts zu tun. Es scheint sich aber um die gleiche Darstellungstechnik zu handeln. Die Menschen verwischen, verschwinden. Das urbane Chaos wird beruhigt, gebannt vom Mann unterm schwarzen Tuch.

Bialobrzeski gibt gern die skurrile Figur aus dem19. Jahrhundert, die sich in den Metropolen der Zukunft bewegt. Er schleppt das Stativ durch die Megacitys, weil es ihm ums Bild geht, nicht um die Technik. „Du musst einfach wissen, welche Mittel du benutzen kannst, um etwas Bestimmtes auszudrücken“, sagt er. „Für diese Arbeit war es die Großformatkamera und nichts anderes.“ Der unhandliche Apparat hat zudem einen großen Vorteil: „Du

wirst viel ernster genommen“, erklärt Bialobrzeski. „Wenn du das erste Mal an einem dieser Orte auftauchst, um Bilder zu machen, bist du noch irgendeine Langnase. Der Apparat aber ist dein Ausweis für eine Art Mission, für etwas irgendwie Hochoffizielles.“

Ob mit schwerem oder leichtem Gepäck: Bialobrzeski ist ein „Wenig-Schießer“. Während seiner Aufenthalte in den asiatischen Großstädten hat er pro Tag nicht mehr als sechs bis acht Belichtungen von ein bis zwei verschiedenen Orten gemacht. Auch seine Auswahl ist rigide. Eine Station seiner Arbeit etwa ist völlig unsichtbar. „Ich habe zehn Tage in Jakarta fotografiert“, sagt Bialobrzeski, „aber kein Foto hereingenommen, weil die Bilder zu sehr an klassische Skylinefotografie erinnerten.“

Von der Sucht nach architektonischer Monumentalität grenzt der Fotograf sich ab. Das gilt auch für die anekdotischen Effekte der klassischen Straßen- und Reportagefotografie. Seine Bildausschnitte sind kompliziert, nicht dramatisch. Er reduziert die Kontraste. Die Farbigkeit mindert er, bis sie ins Pastellige geht. Diese Bilder sollen ihre Betrachter nicht anmachen wie tumbe Aufreißer. Sie sollen elegant mit ihnen flirten. Sie verführen. Hypermodern sein, nicht hypernüchtern. Nah am Alltag und doch nicht plump.

Text von Christoph Ribbat, entnommen aus dem Buch „Peter Bialobrzeski: Neon Tigers“, erschienen 2004 im Hatje Cantz Verlag Ostfildern, ISBN 3-7757-1394-8, © Christoph Ribbat.

Peter Bialobrzeski's Neontigers

Neon is a natural product. And it is a rare one. Its concentration in the atmosphere is1.8 x10-3 by volume percent, or put more simply: 0.002 percent—this is all that exists of the gas, at least on our planet. Synthetic manufacturing? Impossible. That is the wonderful thing about neon light in its classic form: although it represents complete artificiality and cold modernity (very different from the twinkling gas lanterns in Julius Rodenberg’s Paris), the raw material for neon tubes cannot be artificially manufactured.

The same applies to Peter Bialobrzeski’s magical photographs in Neon Tigers. They too are—so to speak—from a natural source. Although they appear to be digital fiction, they are analogue. No mouse click has ever interfered with them, no picture editing has calculated them. Like neon lights, Bialobrzeski’s images only give a hint of the chaos beneath their surface. The crowds that make their way through these megacities are often as invisible as the streams of electrons in the lamps that begin to glow on collision with the gas atoms. Because people are rare in these photographs, the spectator’s gaze is drawn to the artificial light. Sometimes the neon lights of Asia radiate from Bialobrzeski’s pictures as if the concentration of1.8 x10-3 by volume percent were glowing all at once.

Not How It Really Is There, But How It Could Be

“My intention is not to show how it is there,” says Peter Bialobrzeski. “When I photograph it, I want to show how it could be.” When talking about Neon Tigers, he often uses terms such as “dream” and “fiction”. He frequently refers to films, books, computer games: Blade Runner and Star Wars, William Gibson’s novels Neuromancer and Mona Lisa Overdrive, or the computer game Sim City. For Bialobrzeski, all of these images, myths, and fantasies are linked to one another, and he wants the person looking at the image to have the same experience. He wants the facts to disappear at some point, creating the illusion that all of these cities are one city. A new city. A city that cannot be found on the map, but only in the atlas created by Neon Tigers.

“The picture should have the power to enchant. This is what I always aim to do,” explains the photographer. What is clear is

that he is the first to be enchanted by the project, by an imaginary Asia, that for him symbolizes a hypermodern fantasy world. Yet he photographs this world with the most old-fashioned apparatus imaginable: the analogue box camera. “If I did it on the computer,” he says, “it would be boring.”

If you lose yourself in the images in Neon Tigers, you can imagine the photographer as a kind of flying eye. Childlike fantasies are conjured up: of a man who is floating through canyons of highrise buildings, defying gravity, without limits—like in a PlayStation universe. Of course, the daily routine is different. Bialobrzeski arrives in a megacity, looks for a hotel downtown, checks in. Then he sets off, always in the morning. Without his camera—it’s too heavy—he just carries a notepad with him. He goes through the

streets of Shanghai, Shenzhen, Kuala Lumpur, walks in concentric circles around the hotel. Makes notes. Tries somehow to get up high—by climbing upwards over the parking levels. Or by convincing receptionists in hotels and skyscrapers to let him climb up into the vertical world of these metropolises. When he has found a couple of good perspectives he goes back to the hotel. Eats. Rests. Sets off again in the afternoon with his camera— always at the same time, always between four and seven p.m. Squeezes into an elevator with his tripod and glides upwards. Sets up the tripod. Opens the shutter. Sometimes for four minutes, sometimes for eight.

In1839, Daguerre photographed the busy Boulevard du Temple in Paris. Because the exposure time had to be so long, the hectic crowds of pedestrians and vehicles vanished from the picture. Only one man was recognizable: he had just paused for a moment to have his shoes polished. Although the cities Bialobrzeski is interested in have little resemblance to the European cities of the nineteenth century, the way of presenting the city is the same. The people blur, disappear altogether. The urban chaos is calmed, banished by a man beneath a black cloth.

Bialobrzeski likes to present himself as the absurd figure from the nineteenth century who moves through the metropolises of the future. He heaves his tripod through the megacities, because he is interested in the picture itself, not the technicalities. “You simply have to know what medium you can use to express something in particular,” he says. “For this project it was the large format camera and nothing else.” The unwieldy apparatus also has a big advantage: “People take you much more seriously,” explains Bialobrzeski. "When you turn up in one of these places for the first time to take pictures, you are still just some tourist. However, the camera is your pass for a kind of mission, something that is somehow very official.”

Whether with a heavy or a light load: Bialobrzeski is not a “wild shooter”: during his stay in the Asian metropolis, he did not take more than six to eight photos daily, of one or two different places. He also has a rigid selection procedure. One stage of his project, for example, is completely invisible. “I took photos in Jakarta for ten days,” says Bialobrzeski, “but I did not select any of those photos because they were too reminiscent of classic skyline photography.”

The photographer distances himself from the obsession with architectural monumentality. That also applies to the anecdotic effects of street and reportage photography. His image selection is complicated, not dramatic. He reduces the contrasts. He softens the colors to pastel shades. These images are not intended to turn the viewer on like a dumb pickup. They are intended to flirt, with style. To seduce. They should be hypermodern, nor hyperprosaic. They should represent everyday life without being crude.

Text by Christoph Ribbat © from the book “Peter Bialobrzeski: Neon tigers” published 2004 by Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern-Ruit, ISBN 3-7757-1394-8

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#39)

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#47)

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#51)

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#61)

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#71)

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#79)

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#83)

Peter Bialobrzeski - Shenzhen, 2001 (#85)

C-print, ca. 95 x 120 cm (35 x 47"), Ed. 10

C-print, ca. 120 x 160 cm (47 x 67"), Ed. 5